Mohill: a thriving town

Part of a series of articles published in the Leitrim Observer in summer 2020.

'1870: a Society in Transition' looked at the Ireland of 150 years ago as it emerged from the Great Famine.

Most of us have at least a sense of how the Great Famine in the mid-1800s decimated the population of Ireland. Between 1845–51, through a combination of disease, starvation and emigration, the country’s population decreased by some 2,225,000 people.

Leitrim was amongst the worst affected counties. In 1841, Leitrim had 155,297 people; over the next ten years later, the county lost 43,400 people; by 1871, it lost a further 16,335. And the decline continued steadily until 1996, when it reached just over 25,000. Today it is a little over 32,000.

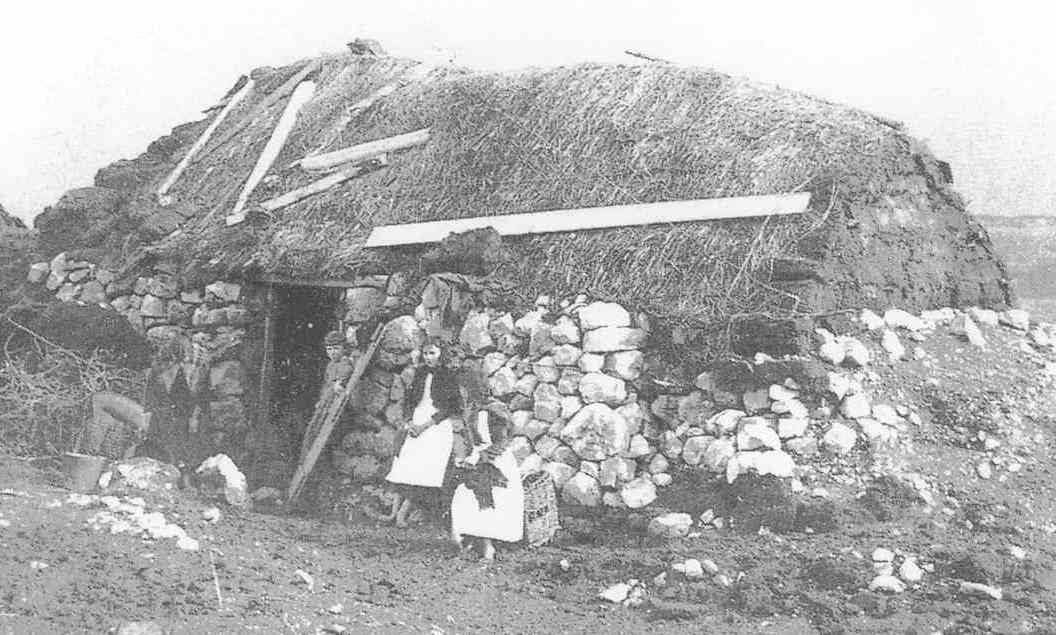

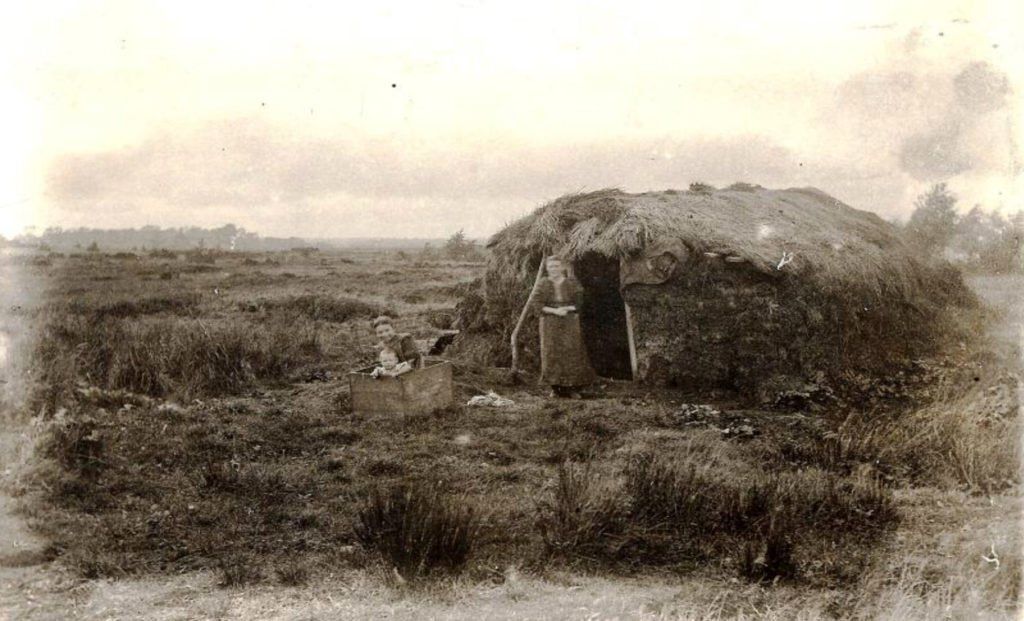

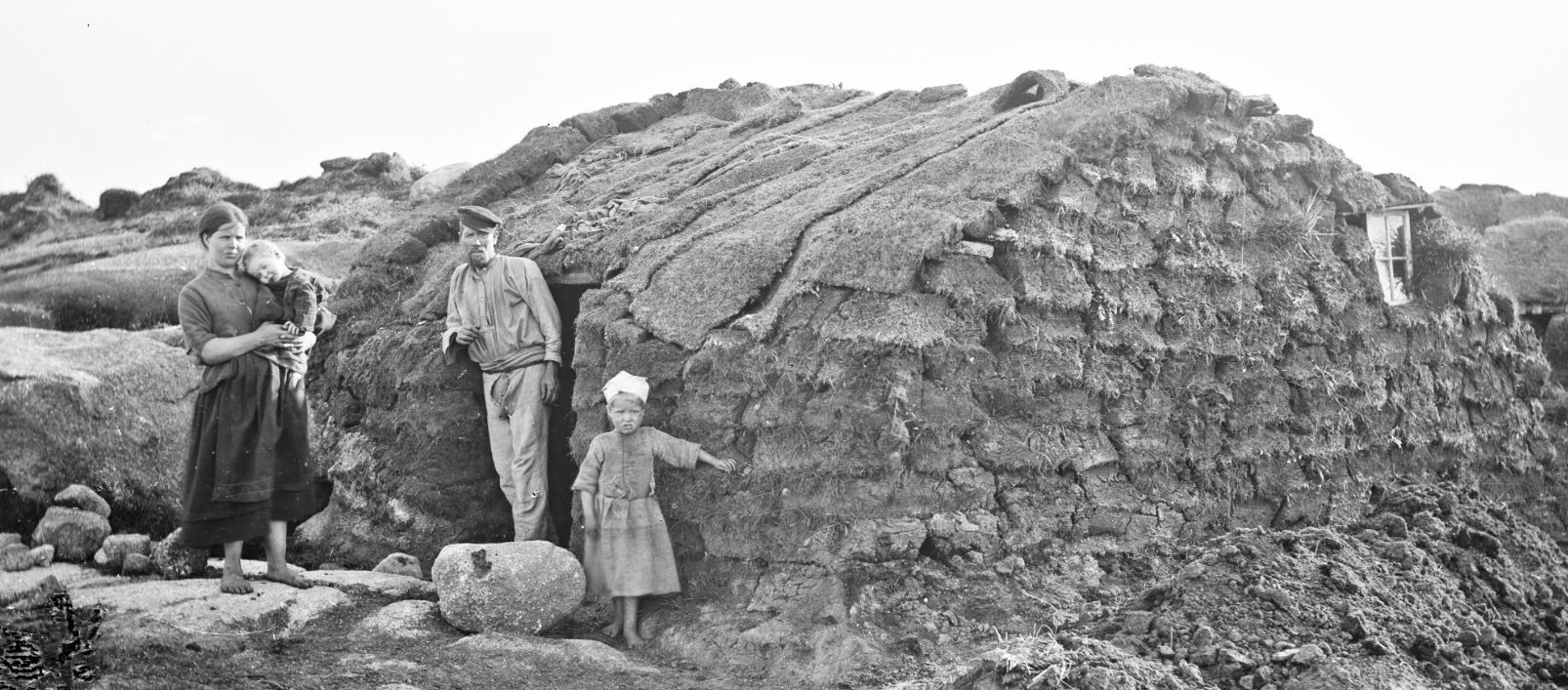

Mud cabins at the time of the Famine in Ireland

Mud cabins at the time of the Famine in Ireland

Button

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

A prosperous, stirring market town

Not every section of the population was affected equally. By the end of the Famine, Leitrim people’s chief source of employment and income had completely changed. While the numbers engaged in Agriculture remained proportionally the same (about 80%), those engaged in the ‘direction of labour’ (i.e. farmers and merchants) tripled from 21% in 1841, to 62% in 1871. At the same time, the number of families depending on their ‘own manual labour’ – poor labourers – was only 25%, compared with 75% in 1841.

The huge shift in employment was mirrored by changes in the type of houses that were inhabited. Big houses and good farmhouses doubled, while the small, one-roomed, windowless mud cabins of the labouring poor were virtually eliminated. In the 20 years to 1861, more than 8 in 10 (over 9,000) of the Class 4 houses in Leitrim were destroyed or abandoned. The poorest, labouring class effectively disappeared.

A transformed society and economy

If they had not died or emigrated during the Famine, the labourers and smallholders were faced with the threat of sweeping land-clearance. For the majority, the solution was emigration. Of those who emigrated from Ireland between 1851-55, it is estimated that 80-90% were illiterate, Irish-speaking, farm labourers or servants. For those who survived or chose to remain in Ireland, the social and economic map of the country had changed for ever. Many of the old values and traditions were lost, as was the Irish language. By 1871, of the 19,486 people who lived in the Barony of Mohill. none spoke ‘Irish Only’, and only 144 – fewer than 1% – spoke Irish and English.

Greater prosperity and sustained development

However abhorrent as policy, the economic impact of the Famine meant greater prosperity and sustained development for those who remained. Travel across Ireland was possible with the railways reaching every county in Ireland by 1870 (Dromod station opened in 1862). People’s homes were more comfortable, and they could increasingly afford to spend money on furnishings and decoration, maybe buying a new deal table or a dresser for the kitchen or fancy curtains for the parlour. The diet of ordinary people continued to be based on potatoes, with wholemeal bread, porridge and milk, but gradually became more varied for a broader number of people as turnips, cabbage, meat and eggs became more commonly available and affordable. The new railway lines, together with an increase in grocery shops, extended the range of provisions beyond what was grown locally. Those with a little spare cash enjoyed the new concept of ‘shop bought’ food, with local retailers providing sugar, biscuits and tea. And they didn’t have to go far to spend their money: Mohill had everything they could need.

Just a few years after the worst of the Famine, the area around Mohill had recovered remarkably. Slater’s Directory 1856 described the town as prosperous and thriving, recording that that its Main Street ‘contains several good shops well-stocked with the various articles of fashion and of local requisites. Great progress is manifest in its general appearance and of its size is considered one of the most stirring, and is certainly the most thriving town of any in the surrounding counties.’

© Fiona Slevin | Last updated February 2024

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.